Important lessons for all in ALICE training

Watertown Middle School completes three intruder scenarios as part of annual drills

Splash photo Watertown Splash

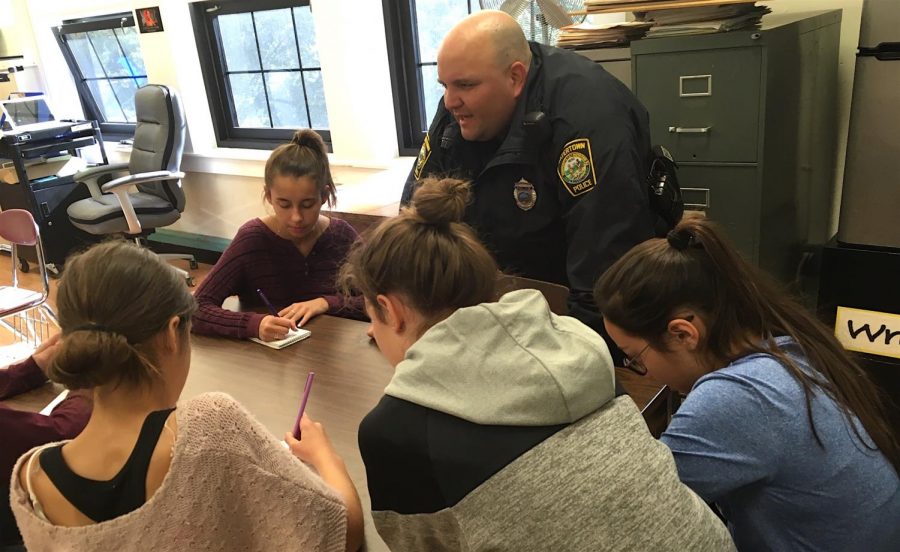

Officer Miguel Colon of the Watertown Police Department talks about the recent ALICE training at Watertown Middle School with reporters from the Watertown Splash.

November 8, 2018

An intruder bursts through your door, you know it’s not real, but it seems like it might be.

Alert. Lockdown. Inform. Counter. Evacuate. All schools in Watertown practiced ALICE training this fall, in case an active shooter ever came into the school.

Every year, the Watertown Middle School goes over and practices this procedure so the students know what to do if an intruder comes in the building. But what happens during these procedures? What procedures do they go through? How long does it take?

To some, this experience may seem exciting since the schedule gets to change and students miss a bit of class, but others are frightened by it.

Watertown Middle School had its ALICE training on Oct. 19, 2018, the same day as the first dance of the year and first-semester progress reports went home.

Officer Miguel Colon of the Watertown Police Department talks about the recent ALICE training at Watertown Middle School with reporters from the Watertown Splash.

There were three scenarios of an intruder in the building and one fire drill. There were three counter drills, one for each grade. Students involved with the counter drill had dodgeballs to use as their object to throw at the intruder. (The police and school didn’t want school objects being thrown and destroyed.) Also, a Watertown police officer used 2-by-4 wooden blocks and clapped them together to impersonate the gunshots.

First, homeroom teachers told students about what they going to do. They were told about intruders coming from different parts of the school, then they were going to hide in the room during one of the intruder scenarios. Lastly, they would evacuate as a school.

“This is just a drill, repeat this is just a drill,” said the voice over the intercom.

There is no doubt that different students and teachers have different opinions on ALICE training, some take it very seriously and think about the reason why we have to practice this, while others think, ‘Yay we get to miss classes and go outside.’ ”

WMS started ALICE training five years ago. There have not been any real lockdown emergencies at WMS, but a shelter in place was held due to a robbery in the area.

According to Jason Del Porto, WMS assistant principal, “The purpose of the drill is to see how smoothly things go and how efficient we are and to create muscle memory.”

Most students knew what to do and what would happen.

“When the alarm came on, it was all expected,” said student Matty Marini.

Afterward, student Lalita Sokhamkaew said of the drills, “I thought it was fun because I know what will happen now, and it’s really good for students to practice.”

ALICE — Alert. Lockdown. Inform. Counter. Evacuate — is not the order things need to be done. According to Officer Miguel Colon of the Watertown Police Department, people in a school need to be flexible and be safe and to go wherever is safe in a real emergency.

“The goal is to have everyone survive in a situation with an active shooter,” said Officer Colon. “Stay safe.”

Officer Colon speaks with experience. He was honored with other Watertown police officers by President Obama for their work in the shootout with the Marathon bombers in 2013. They received the medal of valor, the highest award in public safety in the United States.

Originally the acronym was LICE. A husband and wife — a police officer and a teacher — came up the idea, according to Officer Colon, but added the A because “lice” doesn’t sound good in school.

In one of the seventh-grade classrooms in WMS, a third of the class was bored, another third excited, and the last third was playing paper-io till the alarm. Mrs. McDonagh was serious and talked about the drill a lot.

Ms. Shock’s eighth-grade room is near the back door by the upper gym. It was tense and students talked about it is scary to think about and to have to learn how to do this.

¨Attention!¨ the school’s intercom sounded, as the scenario was explained, students scattered around to push, chairs, tables, and shelves to barricade the door. Outside in the halls, they heard pieces of wood slapping together, making loud “gunshot” sounds.

Mr. Martin’s seventh-grade room was quiet. A lot of things were piled against the door. People were whispering.

In Ms. DiDuca’s seventh-grade classroom, no one moved a single muscle, and the silence in the room was constantly interrupted by the banging noises that felt almost like a lethal disease digging into ears.

One seventh-grader described it this way: “I was getting nervous, my heart started to beat faster and faster and my lungs begging for more air, but I was scared to breathe since I would make noise, and the banging sounds that came closer and closer didn’t cope with my anxiety, which just made my lungs long for more air. My legs were getting sore from crouching so long, but we finally got an announcement that announced ended the procedure. We took down the chairs and tables into their original position, and I calmed down, glad that this so-called intruder didn’t come in.”

In Ms. Kline’s eighth-grade classroom on the first floor of the school, no one came in, but it was very fun. Students all curled up in a corner for one drill and for another they went outside. It depended on where the intruder was located in the building, which was told to students over the announcements.

In one classroom, one student slipped and fell during an evacuation, while other students ran by on way out the door

In Mrs. Lorigan’s seventh-grade room in Cluster 4, near the back parking lot on Bemis Street, the students had to barricade once (in the second scenario) and evacuated twice. The first time they evacuated, it was pretty cold and some kids were kind of fooling around and a teacher got mad.

In the next drill, Mrs. Lorigan’s class had to barricade. A police officer banged the wood slabs together to make the gunshot sound right outside our door. But one girl was laughing because her mom was the officer outside making the noise and her mother had told her she does a funny dance while she does it because no one else is around.

In Ms. Willoughby’s room, in the Cluster 5 hallway on the second floor near the stairwell, her desks are bulletproof, so when students had to lock up in the room, they could build a base and throw glass tubes from it.

In Ms. Smith’s homeroom, right by the stairs, but tucked away out of view, everything seemed normal, calm, nothing dramatic until this room got to experience something few others did.

A police officer came into Ms. Smith’s room pretending to be a criminal. The students were prepared, Mr. Del Porto came in minutes before with a bag of dodgeballs and gave one to each child to defend themselves. Of course, this would not happen in a real situation, but it was still a good experience to practice if this ever happened for real.

The elementary schools also have ALICE training. According to Officer Colon, the elementary schools don’t use clapping of wood to simulate gunfire and they do not breach classrooms. They do the basics of evacuating or barricading.

In the elementary schools, Officer Colon explained, there is “Mother Duck syndrome” because the kids will follow the teachers wherever they go.

The Watertown Middle School did a good job, according to the teachers and officers. The students followed instructions and everything went as smoothly as planned.

“We crushed it,” said Mr. Del Porto.

(For information on ALICE training in schools, go to the homepage: https://www.alicetraining.com/

(This story was reported and written by staff reporters Anika Ziobro, Lalita Sokhamkaew, Julianne Sabino, Caitlyn Ramshaw, Nina Paquette, Rohan Mannan, Liam Lawn, Teagan Janis, Catherine Fleming, Allison Fijux, Bridget Donohue, Noor Dia, Aislin Devaney, Gabriela Bondaryk, Naomi Baker, and Athena Ahmad.)

–Nov. 8, 2018–